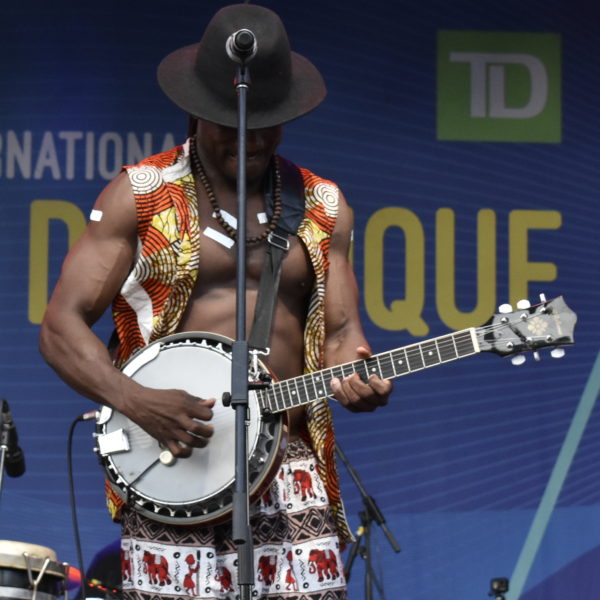

Wesley Louissant—a.k.k. Wesli—is a Montreal-based singer/composer/guitarist/bandleader from Haiti. His stylistic range is deep and wide, and he’s a dynamo on stage, as we’ve learned seeing his performances at the Nuits D’Afrique festival in recent summers. Wesli has just released a big new album called Makaya. Afropop’s Banning Eyre spoke with Wesli twice this year, first at the festival, before the album dropped, and then recently about the album. Here is a mashup of both conversations, lightly edited for clarity.

Banning Eyre: It’s great to see you again. What's new with Wesli?

Wesli: There are a lot of things new for me. I have a new album coming out. Also, I'm creating a studio here in Montreal. I have to put the studio on pause now to go to tour. We have a lot of shows coming up, 10-12 shows from the 30th of July to the 18th of August.

I love your last album, Tradisyon, which we spoke about last time. It's a great exploration of all Haitian folkloric rhythms. What's the new one like?

I always try to give something new on my albums. So this time, I'm trying to mix tradition and modern sounds. This is a lot of work for me to do because I want to keep the authenticity of the roots rhythm and respecting the tradition as it is. But I'm very happy; it's coming out great. The album is called Makaya. This is the name of the tradition as well. Makaya means leaf. It’s from a tradition of the Congo.

We’ll come back to that title. But first, do you record with your band, the same band that you perform with? Or do you work with different musicians and kind of construct things in the studio?

For some of the songs, I record with the band. For some of them, I just isolate myself to make research, traveling in the Caribbean with my laptop and sound card. I'm always trying to record new sounds, discover new atmospheres. So the music is in a never ending world. I am doing my best to explore, and to offer something great.

This summer in Brooklyn, we saw Michael Brun’s BAYO show. He presented so many artists from Haiti that I had never heard of. It seems like an exciting time for Haitian music.

There is a lot of going on for Haitian music. Haiti's doing well on the culture side. For all the Haitian artists, this is the time to show the good side of Haiti. That's what we are trying to do now, because economically and politically, Haiti is going backwards. So this is the time now for the culture and the values—the real values, the tradition values, the African values—to shine.

You go back and forth pretty often, right?

Yes, I've been there last in 2024.

With things so difficult back home, what can Haitians in the diaspora do to help?

The Haitian diaspora has been very important over the years for Haiti. The country was politically isolated from the diaspora and from the constitution. Haitian people think now this is the time for the diaspora to bring back what they’ve learned from the international scene. We are economically very important to the country because most of the money that's going to Haiti is coming from the diaspora. The state over there is very weak, so the diaspora is important for people in Haiti. Now the diaspora should come back home and be useful to the country because the political scene is going down. It needs help, big time.

There was a law that was passed in 1987 that said the diaspora couldn't come, couldn't vote, couldn't make businesses. That was just fear of opposition, but it seems like a very destructive thing. It's much better to have the diaspora coming back. I think there was some constitutional lawmaker who didn't want the Papa Doc era to end. They didn’t want some dictator coming from the diaspora to come back to Haiti. The tonton macout (a much-feared paramilitary group), didn’t want the diaspora to come back. That's why they created this law, but now it's not very useful for us because there is no more tonton macout, so we have to change it. But we need a functional government to change that. So far we don't have that, and now the Haitian people see the weakness. They need us, so they are aiming to get us involved in what is going on in the country now.

That’s interesting. It’s also interesting that Haiti is so strong on the cultural side right now, while the government is so weak. I think of the Congo as a country that produced such strong music under a terrible government. Sometimes struggle brings out the creativity, maybe a feeling of urgency. You have to rise to the occasion. Do you think that's the case at all with Haitian music these days?

Of course. We want to bring culture to the political scene, on the good side and in a good way. Because the political scene is bad, so we want to give a response with art and culture very strongly. That's the goal.

What are you singing about on the new album?

The messages are about coming together. When you say Mountain Makaya, that’s where the slave rebellion started. I told you that makaya means leaf. Those leaves have a lot of medicine from trees for the slaves to cure themselves with natural medicine. The Makaya is very significant to us. That's where the leaders of the first nation were hiding and practicing medicine and all kinds of culture. African slaves were going there and joining the first nation that started the rebellion. It’s an amazing story. That's why I call the album Makaya.

Beautiful. So for the show tonight, tell me about your band, how many musicians will you have tonight?

We have a bunch of musicians tonight. We have the brass, also keyboard and drums, guitar, bass and percussion, and then we have backup singers and dancers. Also, we invited some Haitian artists to join us. We are going to offer something great tonight.

Excellent. Well, you are lucky there are so many great Haitian musicians in Montreal.

That’s true.

Fast forward four months, and Makaya is out in the world. It’s a remarkable album, 24 tracks divided into five thematic sections: Electro Section, Organic and Festive Section, Troubadour Section, Afrobeat Section, Traditional Haitian Rhythms. The variety and range are impressive, and there isn’t a weak track in the lot. Having had time to listen and reflect, I needed to talk with Wesli again. So I reached him over Zoom in mid-December for a follow-up.

Banning Eyre: So Wesli, I've had some time to listen to this album now. Man, it's really quite a piece of work.

Wesli: It was lot of work.

I can only imagine. It's huge. When we spoke in the summer, you said you were looking to mix roots with modern sounds. You’ve certainly done that, and so much more. How did how did you come on the idea of presenting the music in sections?

It was a long time process for me. I wanted to give Makaya the value it deserved, because for Haitians, it means a lot to us. It means resistance and resilience, and also victory. So I wanted to have an album that represents victory, resilience and freedom. So I come with all the electronics and the modern sound that I said I would put in it. But it was not enough for me just to stay in there. I wanted to go further. Inspiration came. Lyrics came. Great music came. I have a great connection with my roots in African culture and the Igbo, the Congo and everything that makes my culture and my tradition good. I didn’t have to search far, I have the richness of Africa in my blood.

How long did it take you to record all this? It must have been many sessions.

A lot of sessions, and we didn't even put all the song on the album. We had to choose 24 out of 30 songs. So there were six we left aside. So yeah, it took a long time. Everyone in studio was there for the cause because it’s is a noble cause. When you think of what Haitian is going through now, they deserve more, they deserve good things. So we had to honor the Haitian culture and people because they are going through a lot of things in this moment.

I remember having a discussion with Jacob Edgar from your record label, Cumbancha. This was just after your last album, and he said, “Wesli, man. He just keeps coming up with songs. We can't keep up.” Well you’ve proven that. I hope people in Haiti get to hear this because it's really exceptional. Let's talk a little bit more about the title. Makaya means leaf, and leaves are associated with healing. Makaya is also a sacred symbol in the Vodun religion, and it's the name of a mountain range where the Maroons hid before the Haitian Revolution. That’s important for the stories told on this album. And all that is a lot to find in a single word. Did I miss anything?

“Makaya” means “leaf” in Kikongo. Congo is a big part of our culture. From December 1 to 31, we are in the period of Makaya in the Vodun tradition. It’s like getting a leaf bath for the end of the year to be purified and get cleaned for the new year coming. It has to do with leaves falling off trees. It’s about renewal. We use a secret leaf. We put leaves together in a pail and then make a mix with them. Then we shower the water on people. It’s a shower to purify so you can be born again for the coming year.

It's an annual thing.

Yes. An annual thing. And secondly, Vodun practices took that leaf from this mountain range. The Makaya mountain range is a forest, full of trees. That’s where people went to organize the revolution.

In 1804. It all fits together now. Wesli, you sing in many languages on this album, French, English, Kreyòl, Yoruba, Fon… Do you speak all these languages?

Well, the African ones are not spoken in Haiti anymore. They are part of Kreyòl tradition; they are singing languages, not spoken. There is Kikongo; there is Igbo also; there is Yoruba there. There are a lot of songs we sing in Mina and Ewe also. These are llanguages that stayed in Vodun tradition in the lakous, languages that we sing but we don't speak. We know the meaning of the songs and which kind of culture and tradition that is connected to each one, to but we don't speak them anymore, unfortunately.

It's fascinating that they're preserved in the music. You mentioned lakous. A lakou is a kind of cultural house, right?

Yes, a lakou is a physical house, but it can be a tree also be a space, a tree or a gazebo. Bwa Kayiman was a lakou. That’s where the first slave rebellion started with Dutty Bookman and Cécile Fatiman. Bwa Kayiman wasn't an actual house; it was a tree. So the lakou is just a place where tradition has been preserved to serve the people.

I see. So a language like Ewe could be preserved in a particular set of songs that goes with a particular lakou. Does it work that way?

Yes. It works that way. Lakou is a Fon word, and it means “come together.”

Cool. Let’s talk about rhythms. I've followed Haitian music for awhile, and have always heard about some of these rhythms, Rada, Petwo, Lakou Kongo… The notes for this album talk a lot about a rhythm called Yanvalou. Tell me about that one.

Yanvalou is a 6/8 rhythm coming from Dahomey. It's from the Rada rhythm family. All the 6/8 rhythms are coming from the Rada family; all the 4/4 rhythms are coming from Congo family.

That’s helpful. 4/4 is Congo and 6/8 is Rada.

Yes. All the 6/8 is from the Rada family. In Rada, you have the Palo, you have the Nago, you have also the Dahomey. There are a lot of 6/8 rhythms in this family and Yanvalou is one of them. So then you have the Congo family. The Petwo is from the Congo family; the Igbo is coming from the Congo family, and there are a lot more.

I'm curious about how you learned all this. Was it part of your family tradition or is this stuff you've learned through research that you've done since?

I learned all this from the family tree, you know, oral tradition. My dad gave me a lot of knowledge. He talked about all the rhythms with us and played music with us when I was a little boy.

He was a musician.

Yeah, he was a musician and also into the oral culture in Haiti. You would find all the moms and dads there and talking about African culture, how it preserve the way the Susus, the Mandings, all that. It’s talking to the kids before we sleep. So your mom says, “You have to know where you come from, where you are, what you're doing here, why are you here.”

Do you think right up to this day that most Haitians understand at least some of this stuff, because they get told it by their parents? You are very knowledgeable about these things, and I'm wondering how typical that is. Does an ordinary Haitian kid know all this?

Haitian culture nowadays—they don't tell much of that anymore because they’ve become Americanized and then they try to be something else. There are a lot of schools that don’t want the kids to go through that path of tradition and know the knowledge of the ancestors and cultures. Me, I grew up in a family where they value that a lot and they gave the knowledge to me. But most Haitians in this moment and the generation X or Z or whatever, and they don't have this knowledge anymore because it's been disappeared. Most of the culture now is social media and consumerism and materialism. So that's why I come with this Makaya, to bring them back to the roots so they know where they come in from. I want to reiterate this kind of culture, this kind of oral transmission of culture just for them to remember: This is who we are. Don't forget who we are.

I wonder if that change in culture is part of the reason that there are so many problems in Haiti now. If people remembered this history more, maybe things would be going different, right?

Yes, absolutely. If they remember where they're coming from, they will remember their culture, and they will be better off. It's like all the country has been materialized. They don't see the spiritual side and the cultural side. They forget who they are. As I always say, knowing your culture doesn't hurt you in any way. It doesn't stop you to become famous or become fortunate. You can still be fortunate and know where you're coming from and know your values well, and transfer your values from generation to generation. That's what Makaya is about. This is a part of reconciliation, part of coming back to the roots. This is your time now to say who you are in the middle of the Caribbean now, and where you want to bring this first Black nation in the next 50 or 100 years.

You mentioned social media, American influence, foreign influence... I understand those factors. What about Christianity, evangelicals, missionaries and the like? What is their role in this forgetting of culture and history? I'm sure there are lots of devoted Christians in Haiti, but can you be both that and also an adherent to Haiti’s traditional religion? Or is it a conflict?

You can be both, but the evangelicals don't want you to be both. They came to Haiti to destroy tradition Vodun and sisters spirituality. They don't want that at all. They say if you are doing this or your mom talk about the Igbos to you, you are evil. So they don't get along with that. In the big cities there are a lot of evangelical churches, and they go everywhere. They are educating kids now in schools. That's why many Haitians don’t know where they are going. It’s a continuation of colonialism and neo-colonialism. So I'm against that. I always tell them they have to help Haitians find solutions for their problem instead of adding more problems to the problem.

Wiping out traditional culture is never going to help, is it?

That's it.

Okay. One more question before we get to the songs. I’ve been reading the various notes that you provided for this album, and sometimes I think I'm hearing kompa, but then I read the descriptions that mostly talk about merengue and zouk and soukous. Maybe I hear those kind of rhythms think, “Haiti. Okay it's like kompa.” What is your take on kompa?

Kompa, I love kompa. This is the most popular rhythm in Haiti. So if you listen to the album, there is a lot of influence of kompa. The twoubadou (troubadour) music is the roots of kompa. You hear the maracas with the cha-chas and everything. These are the roots of kompa. So we have the mereng, which is a kind of kompa. For sure, the Dominicans popularized it as meringue. In Haiti, it's called mereng. It's been there for 100 years, since the 1920s. Issa El Saieh played mereng. And Nemusico was playing mereng. Luman Casimir was playing mereng. It was like a carnival for the people. The mereng was the faster rhythm. It’s also called cadence kompa. But all the merengs are kompa.

It's a family of styles. In Montreal, I spoke with the guys from the band Baz Compa and they were telling me about different varieties of the style, like kompa direct. I guess all these things are coming from similar origins.

Yes. Kompa has different varieties: kompa direct, kompa love… A new generation started in the ‘90s. Kompa direct is a kind of mix-up kompa and zouk, talking about love.

When we first started to work on Afropop in 1986, and when we went on the air in 1988, the Haitian music we heard was all racine. It was Boukman Eksperyans and Boukan Ginen. I thought at that time that the kompa of Tabou Combo and Coupé Cloué was just older music whose time had passed. But clearly the genre survives anew. As you say, it's the most popular Haitian pop music.

Yes, it's become pop now.

Well, it's good dance music.

It is good dance music.

Let me ask you about a few of these songs. There are too many to cover, but let’s start with “Bonton Iyalélé.” There's a lot of things going on here. This is one of the 6/8 rhythms, and there are multiple languages. Also you are producing here with Afrotronix, the Chadian artist in Montreal. I particularly like this song. What can you tell me about it?

“Bonton Iyalélé” is a song about good times. You have to remember the good times whenever you are having a bad time. It’s about the resilience of the Haitian people. I wanted to make it with Afrotronix because Iyalélé in his language means bontemps, good times.

There's a sound in that song that sounds almost like wood creaking, like the hull of an wooden ship in rough waters. It’s a great sound. What is that?

It's like a calabash mixed with a bunch of electronic sounds, calabash and bass. We mix them together to make like a kind of rude, electro-organic sound.

That song also goes back and forth between a fast feel and the slower feel.

Yes. It’s nago in the beginning, very slow, and then when it goes fast, it becomes Dahomey.

I love the three twoubadou songs, “Chacha,” “Maknay,” and “Lanmou Nou.” That last one has a great trumpet solo on it. Who's playing that trumpet?

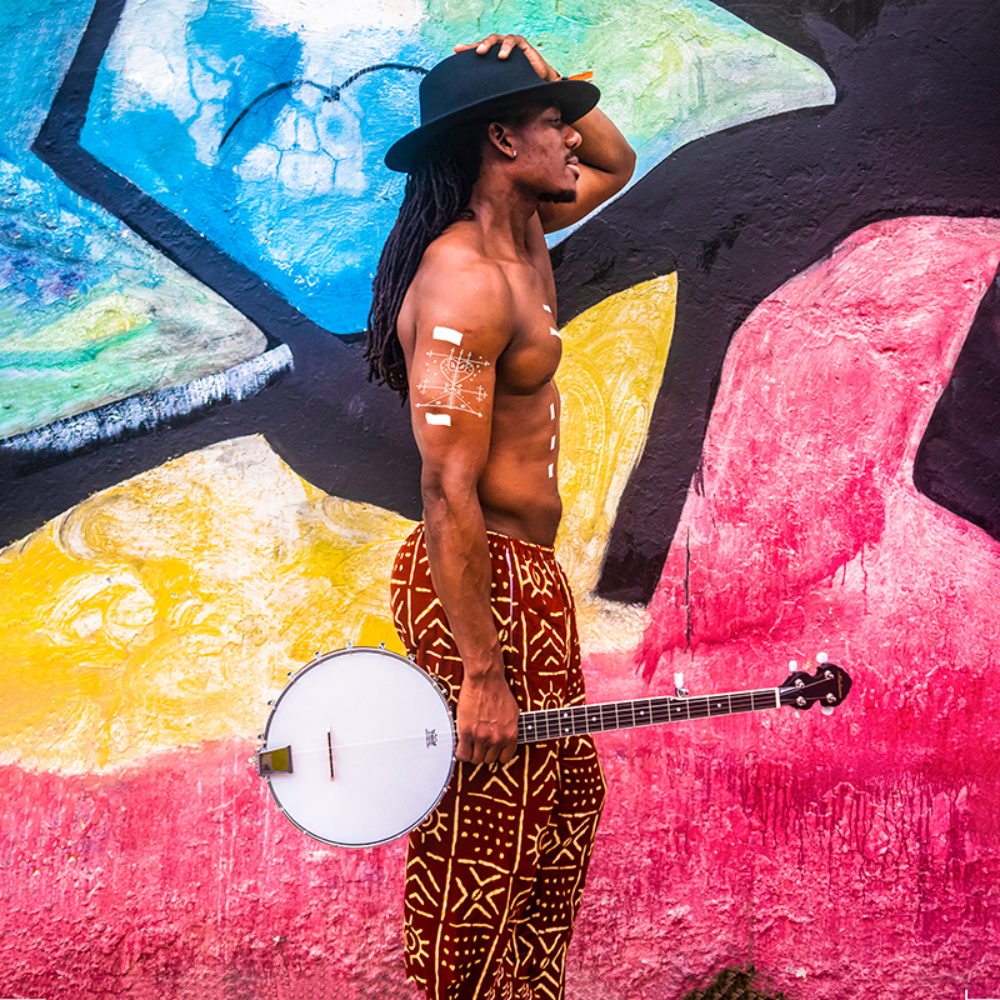

The trumpet is played by Togolese trumpeter called Kokou Damawou. I think you saw him on stage with us. He’s a really good trumpet player and on the “Lanmou Nou” song, it's a kind of twoubadou with banjo and maracas and all that mixed together with guitar and make a unique sound. We didn't put any electronics on it. We put a kick at the end, and also the trombone solo alternating with the trumpet solo.

“Chacha” is even more spare.

Yeah. Mostly maracas. I did that with Tamara Suffren. We talk about love. The twoubadou tradition is about welcoming. When you welcome people in your house, you play the twoubadou music for them. It's an acoustic music. If you went to Haiti in the ‘70s, ‘80s, even now, you have a twoubadou chacha band at the airport to welcome you, with the banjo and the manumba (sometimes marimbula) bass that you sit on. It’s like a big Haitian kalimba that goes boom, boom, boom. It's all acoustic sound and then it's amazing. I really love doing that kind of music because most people don't know this side of Haiti.

I love that too. I'm a big acoustic music guy, so it's nice to hear that element in your mix. And the banjo has such an interesting history in Haiti. I’m fascinated with the banjo. I recently spoke with the author Laurent Dubois, who has written a book about Haiti, and also one about the banjo. He says the instrument thrives in places where cultures are colliding and mixing.

Yes. It's like a kind of federation music of the world with the banjo. It's a sound like that calls every culture, as well as the accordion. That’s what is interesting in twoubadou music. We use folk instruments, like banjo and accordion, mixed with African instruments and make something unique to Haiti. Haitians have been playing this music for years. And you know, the banjo has been preserved through the sugar cane fields. So many Haitians went to the cotton and sugar cane fields in Cuba and the Dominican Republic, and their recreation time was playing banjo. We have the banjo with nylon strings, fishing line. We have the alto banjo, the bass banjo and the soprano banjo.

I've done field work in West Africa and Mali and Senegal and those countries have this whole family of ancestors of the banjo. I don't think there's any one ancestor, but there has clearly been a transmission. The African family of lutes includes big ones, small ones, one string, seven strings, four strings… Many varieties.

We have the four strings in Haiti, but we don't tune them the same way. In New Orleans, they tune it as a violin, but in Haiti, we tune it as a ukulele. In Haiti, our banjos are all pentatonic.

Have you ever had a chance to travel in West Africa, or to play there?

Yes, I did my Masters with Djessou Mory Kanté in Conakry, Guinea. I went there for six or seven months. He was my mentor.

Fantastic. He’s such a great guitar player.

Yes. So I was learning Mande guitar, and trying to make something with Haitian music. He used to call me Haiti Diabaté. I'm the Haitian Diabaté. [laughs]

That's wonderful. I love that. I lived in Mali for a while learning Mande guitar. I can relate!

It's a royal music. For kings and queens. Very rich.

Let me ask you about your brass section. They are very versatile. I love the way when you're doing Afrobeat, it really feels like Afrobeat horn arranging, and when they play salsa or funk, it’s spot on. Is this the same brass section all the way through?

Yes, it's the same brass section, but there are different arrangers. For the Afrobeat, it’s Kokou Damawou from Togo. He used to be part of the Gangbe Brass Band. He's the one who did the Afrobeat arrangement for me. I told him I need a baritone sax, I need a trombone, I need tenor saxophone, and he was like, “Okay, saxophone tenor is going to play this line, and this line is for the trombone…” He was the one that had the sound; he could lead us to that Afrobeat sound.

I also have Rachel Therrien as trumpet player as well. She helped us with arrangements. And then Jean-Francois Ouelette and then André Desilets for the more modern sound, or salsa or things that were more funky.

Wow. Gangbe Brass. What a wonderful band. I see they just did a new album. I know that some of those guys were living in New York for awhile. But the current version of the band has a new album, and they sound great.

Kokou lives in Montreal now. He’s one of the kids of the fathers of the Gangbe Brass Band. The fathers gave the band to their kids; they passed it on.

That makes sense. It’s a cool concept: brass bands and Vodun melodies and rhythms. Let's go to the Afrobeat songs, “Afro B,” for example. The song is about immigration, and that is a very big theme these days. I know that many West African artists have written songs telling people, “Don't go to Europe. Don't go to America. It’s not what you think it is. You're going to have a hard time there. Stay here and build your country.” That's a very common message I hear in singers from those countries. What's your message here in this song, “Afro B”?

My message is explaining to our people that immigration is very hard. To leave your country, leave your culture, adapt yourself, adjust yourself to a new culture and a new way of life is hard. Sometimes it takes you 20, 30 years to learn, and then you still have 30 years, 40 years learning this culture that you are in. You never feel home because you are connected to Africa. This is “Afro B” meaning Afro Best, but I didn't put the “best.” It means that Africa is the best, and our country is the best, so you have to stay home.

At the same time I send a message of reconciliation as well. We have to stay to build a nation. It doesn't take 10 or 15 years; it takes one generation to build values for the next generation. Someone left the country to go to another country to search for a better life, but all other richness are at home; you only need the knowledge to understand this. I think that Christianity and Catholicism have blinded us to the value we have at home. So I also say, “Don't listen to religion. What you have at home is enough to build richness. Your country will be better and your generation will be better.”

You’ve been in Montreal for 25 years now, so you speak from experience on that subject.

Yeah, I speak from experience. It's a fact for me. You know what? Even the Canadians, they know that I want to give back to Haiti. I’ve learned a lot here. So it makes me more able to understand how everyone can live together with different religions and different ideas. Tolerance makes me a better person. So I always say, this is what I'm going to bring back to Haiti. We have to have resilience because Haiti needs us. They need the diaspora.

That brings me to where I want to end up, which is, what's it like when you go back to Haiti now? Have you been able to bring your band to perform there?

Yes. The first time I brought my band in Haiti was in 2012-13. Some of my band members were born here. Some of them left Haiti a long time ago. Some are coming from Africa. For the Haitians, it was a redemption coming back to see the people were waiting for us because I did an album called Liberté Dans le Noir. Everyone was waiting for that album in Haiti. We did a couple of concerts and we got full houses. Everybody in the band was crying, saying, “Yo, this is what you've been talking about for a long time. Now I understand it. I can see it. I can feel it.” You can never forget that.

So now with my band, it's become a mission. They went to Haiti to see the values that I want to preserve. They are all now in the boat with me to defend the cause and push the cause all over the world. So the second time I went with my band, it was for the Carrefour Fiesta in 2015. We played a big sports stadium in Carrefour. We play also in the middle of Port au Prince, and we played the jazz festival with Joël Widmaier and the musicians from Zèklè, and it was really good. I go to Haiti every time just to make research. All my family is there. I'm going now to see my mom like in two weeks. So I'm going to spend Christmas with my mom. It’s something I will never leave behind.

Are people in Haiti are able to hear this album? Does it get played on the radio, or is it all through social media? And do you think it will be possible to bring the band to play again? It must be particularly difficult now.

It will be difficult for now. That's why we want peace for Haiti. In the album, we call for Haitians to put themselves together again like they did in Bois Caïman (Bwa Kayiman), like they did in Makaya to bring a new freedom to the country from neo-colonialism. It's been a long time. We thought we finished the job in 1804 and 1805. But on this album album, I send a message to say it is time to go back to the 1804 mentality, to regain our freedom and get a new country that is good for everyone

Do people hear this message mostly through the internet and social media? Is there any radio play?

It is going on the radio. They have received the album. And now we are counting the days to go back there and to deliver it live to them.

Well, I hope you get to do that. It's about the best album of Haitian music I've heard in a long time.

Thank you so much. I will tell the Haitians that for you. They will be happy. You know, I was waiting to release it on the 18th of November, because the 18th of November, 1803, was the victory over Napoleon’s army in Haiti. So I waited for six months to release it on that date. That date brought a lot of luck to Haitians as well, because the national team qualified for the World Cup, and that same day, I released the album.

Well that was worth the wait. It’s great to talk with you again and if you're ever coming by New York, be sure to let us know. We'll be in Montreal next summer, if not sooner. Have a fantastic time in Haiti and congratulations on a wonderful album.

Thank you, Banning. Thank you so much.

Related Audio Programs