The African Diaspora International Film Festival has just completed its 33rd year—and it has reached a turning point at exactly the moment the world’s relationship to storytelling is being transformed. Technology has shifted exhibition, production and attention: everyday people are now content creators, character narrators, and archivists of their own realities. Audiences are no longer gathered only by geography or a single annual calendar slot; they are formed by habits, platforms, and communities that can be built year-round.

For ADIFF and ArtMattan Films, that shift meets an older truth: the work has never been only about an event. It has always been about infrastructure—screens, access, and the right to be seen. Over three decades, the festival’s curatorial life has quietly generated what most institutions claim to want, but few actually possess: an archive with depth. Not a handful of “hot titles,” but a long arc—classics, experimental work, contemporary urgency, and films that don’t fit the mainstream’s narrow idea of what African and diasporic stories are supposed to look like.

The festival is valuable because it is a living archive of African cinema(s). The term African cinema(s) explores the interactions of visual and verbal narratives in films from and about Africa, and I expand the term to mean all manifestations of visual and performative literacies, formats and genres with metaphysical roots that originate in Africa.

This year’s New York festival packed 71 films from 41 countries into roughly two weeks—a sheer density of a continuum of Pan African cultural memory. Alongside the in-person marathon, the ADIFF Mini Virtual Festival returned with 20 films available online across the U.S. and Canada. In other words, the festival already lives in two realities at once—the embodied ritual of gathering in a theatre, and the dispersed, borderless diaspora watching from wherever we are.

The opening night film this year was The Dutchman, a remake of Amiri Baraka’s riveting classic psycho-race-thriller. This new rendition of The Dutchman, directed by Andre Gaines, opened the festival with a Q&A critique on the symbolism, characters, and themes surrounding racial oppression and identity in American society and culture.

The closing night film was another remake of the life and times of Frantz Fanon in a powerful biographical drama on his revolutionary years in Algeria.

These two films are bookends illustrating a Black world digging deeper into its collective consciousness without restrictions on space or time. Personal cell phones and the human impulse to network on social media have democratized creation and access to information, making it continuous, ever-present, and now all-knowing as a collective endeavor. Still, these devices are also rewiring our brains into dopamine hits, training through 1-3-5 second soundbites—history reduced to “momentary disposable content,” identity reduced to a caption, complexity forced into a reel.

This is why the ADIFF archive of African cinema(s) is critical at this moment in time to fill in the gaps of what is being discovered. AI has begun to open archives—digitize collections, reveal neglected and hidden records, and map lineages of buried in scholarship—revealing what feels like a bottomless pit of information about African existence on the planet. We see and hear more evidence that the African story is older, wider, and less containable. We have pushed beyond the familiar modern frames of “diaspora” as only the afterlife of the Black body from the Atlantic, beyond slavery as the sole organizing narrative, toward a longer arc of initial movement throughout the green Sahara in Africa. This would apply in the north-south axis from the Nile to the Limpopo, where, as trade, travel and co-migratory patterns between humans and animals, there is a cultural continuity where movement, encounter, ritual, trade, intermarriage and conquest left intangible cultural heritage.

And this is precisely why ADIFF finds itself at a watershed and has opened the archive with its own TV and VOD platform. The festival turns 33 just as technology is transforming storytelling at every level—everyday people becoming content creators and narrators of their own realities. At the same time, institutions scramble to keep pace with the new economics of self-motivated knowledge production, attention, distribution, and organic community.

That archive has roots. In Burkina Faso, through the orbit of FESPACO, and through the influence of the late Clement Tapsoba, whose criticism, editorial work, and belief in African cinema helped shape a generation of filmmakers, writers, and programmers. The Burkina story matters here because ADIFF’s story is not only a New York story. It is a diasporic story—built through movement: Burkina to Paris, Montreal to Harlem, classrooms to theatres, festivals to distribution, and now into a new container.

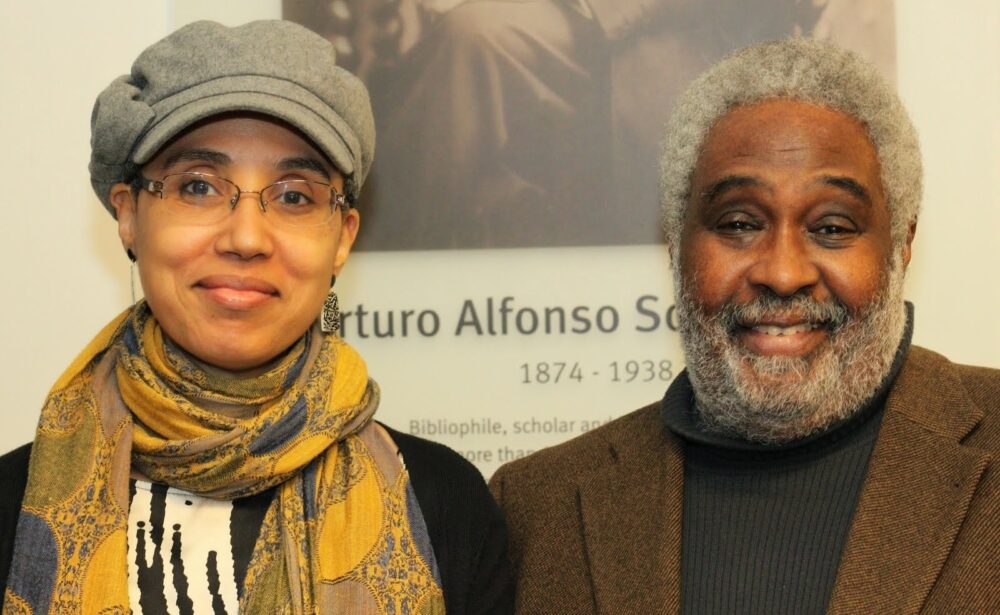

I sat down with the co-founders in the midst of the 33rd annual festival.

Africa Diaspora International Film Festival Reel

Diarah N´Daw-Spech: It’s been awhile.

Mukwae Wabei Siyolwe: Can you believe it’s been 30 years?

Yeah, he’s laughing. It doesn’t make us feel any younger, right? That’s amazing.

Reinaldo- Barroso-Spech: I just can’t even believe it. It’s like, what? How? How did that even happen? You know?

Of course, he hasn’t changed. No, he hasn’t changed a bit. He looks well—both of you.

DNS: Thank you.

Congratulations. You made it to 33 years. Amazing. And I’m mad that I’m only catching you now at Afropop Worldwide, because I’ve been there for about four or five years—and I don’t know why I’ve never reviewed any of your festivals. So it’s time to do a feature.

Thank you. Yes. It’s better late than never.

Oh yes—better late than never. And you still have exactly the same connections with Columbia University.

RBS: Yes. Well, I’m no longer teaching there. I retired from teaching. But we have a connection there. We have a program—an extracurricular program. The last weekend of the month, we show films. We invite guests. We have some munchies and films. It’s open to the students—the whole body of the students at Teachers College—and the community is invited. And that program, as Diarah said, has been around for twenty years.

Some of the showings of the festival take place at the university as part of that same program. The program hasn’t changed. So we’re still there. And it’s less demanding than the festival, but it’s a connection with the student community. Columbia is very particular—I’m telling you. Based on my experience, I taught in different universities and colleges here in New York City, and Columbia is peculiar.

The program started with the notion that someone understood the students at Columbia are disconnected from many, many, many things. These students need to know a little bit more about Africa, about Black people, and all that.

From my experience teaching there, just to give you a silly anecdote: I remember on one occasion I was using a film from Uruguay, a little country in South America, and there were Black people in the film. The protagonist was a little Black boy. And a couple of students said, “Oh, we didn’t know there were Black people in Uruguay.” Well, slavery was a large phenomenon in this part of the world. Black people are in every country in Latin America and the Americas in general.

So the person at that time in that department understood the need, and the program continues with the same intention. And that is also part of—perhaps you’re not aware—the various platforms we have created in other cities.

I do know that, but tell me more.

Today, in addition to the activities we have in New York City, we have an event. It’s a short event—three days—in Chicago. We also have another three-day festival in Washington, D.C., and another in Paris, France.

Genial.

In different moments of the year, we travel to those cities with films, filmmakers, producers, and on some occasions, we present all we do. One of the things we have discovered in this work is that the need is large. Wherever we go, we have an audience—and it is a diverse audience. More people of African descent are interested in the work we bring to those cities. The interaction confirms the need for platforms promoting and showcasing this type of work.

But it is not opening doors easily for that type of cinema, especially African films. This is complicated to understand. Because in this country, we have a critical mass of people of African descent with the purchasing power to watch a film. But the infrastructure is complicated. When we talk about theatres—and then when we talk about other platforms—it’s also complicated.

The positive part is: when we started in 1993, we didn’t have those opportunities to go to other cities and find an audience. So Black films, and African films in particular, have more room today than they did thirty years ago.

Another positive part is that technology has democratized the making of films. So we have more variety. You mentioned classics like Sarraounia and Yeelen. Today, there are more people making films, more people with the potential to make films of that quality. I was telling Diarah: I feel the great African film has not been made yet. And perhaps it’s okay. Perhaps you don’t need to have a “great film” to have a great production. Let’s see how it goes.

The players are diverse—in Black cinema, in African cinema. The discussion around African films is complicated. In every unity, you have the positive and the negative. The positive part is: we are talking more and more about African films, there are more platforms, and there is a younger generation who didn’t know much about Sarraounia, didn’t know much about Yeelen, didn’t know anything about an old film from Nigeria. They come. Let’s see how it goes. We are part of a movement of images and ideas.

It is unfortunate—you mentioned Clement Tapsoba is no longer around.

Clement Tapsoba was an incredible source of information and knowledge to us. When we went to FESPACO, he understood where we were coming from. I am not a frequent person in those circles. I am someone born in Cuba—someone who is not running away from his Negritude—and someone who is talking about the revolutionary importance of African cinema.

I learned with time that I was not a regular kind of person in certain circles, and with Diarah, it is the same thing. So we created this combination here—this structure that is beyond stereotype.

One of the things I realized when we began: we came from different walks of life. I was born in Cuba. I was a professor of French in Cuba. When I landed in Paris, the fact that I could speak French fluently helped me meet a lot of people. And at the university, I was attracted to the diversity of Black people I couldn’t find in school—people from the Caribbean, people from African countries. And then I realized the power we have with our stories, with our way of presenting the world, with the understanding of things coming our way.

And when I came here—when we came here—I ended up teaching because this is what I am. I am a teacher. And I was very surprised that, as a teacher, I was some sort of an oddity. Because I was teaching French, I was teaching Spanish. Since we are people who love cinema and Paris is a city where you can see films from many places, we were intrigued by the fact that in New York City, we did not see the diversity of films we used to see in Montreal, because there was a festival there. In Montreal, we watched international cinema. It was in Montreal where we met Haile Gerima, at the time of Sankofa.

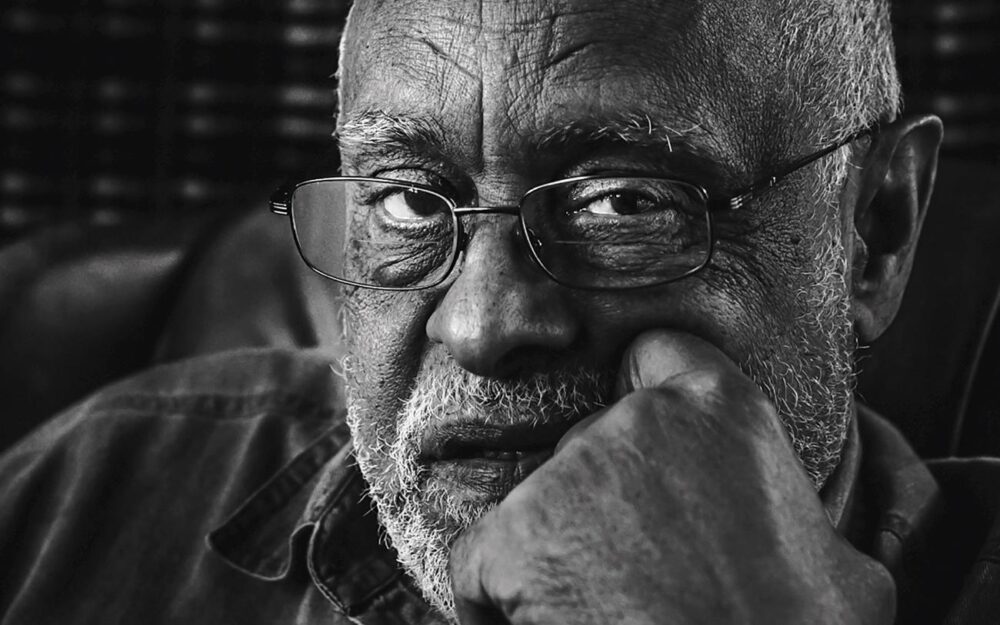

IMAGE: Haile Gerima

He was looking for a screen in New York City. I said, “Okay, we have a festival. We begin this year. If you don’t mind, we can show your film.” And to be honest, we did not know who Haile Gerima was. We didn’t know how important he was in the Black film movement in the United States. We didn’t know how important the syncretic work he had made was. But he was cool—and he was looking for a screen because he had really been rejected from all of the venues that would normally show art films, auteur films. He was rejected. So we gave him an opening in New York.

Yes.

And we continue. It was a big moment for us—for that film, that auteur. We realized that we are in something really, really big here. Because on my side, the need to have those kinds of films in the city was more educational: people need to see this, to be acquainted with these cultures and people. And on the other side, she was going to school, working on her MBA.

What abut you, Diarah?

DNS: I was born in France. My father is from Mali. My mother is French. I grew up in the suburbs of Paris—in those cities they built in the ‘60s and ‘70s to house immigrants brought over to work cheaply in factories, to do the jobs French people didn’t want to do. I grew up in a place with very mixed kinds of people—neighbours from Algeria, from Guadeloupe and France.

The city was also run by a communist government. They were very into culture, into outdoor things, etc. So I was lucky: not with money, but access to culture, to knowledge, to education. I took some Russian at school—it was hard. I took Spanish and English—that’s how I’m able to manage.

In my family, there was a big interest in culture. My mother is French, my father is from Mali, so it was mixed culturally with exposure to a lot of things from all over the world. And cinema was always a big part of what I was exposed to as a child—going to see Yeelen in a small Paris theatre as a teenager, Kurosawa, Godard, all that.

Reinaldo and I connected because we had a similar interest in cinema. And this encounter—two people with similar origins but different developments—made us realize this type of work could be empowering for all of us.

Yeah, absolutely. Why do we do the festival? There’s a moment we all converged. I think Third Cinema was the situation we all came up in—this idea that there’s a cinema outside Western cinema, that the global majority has cinema too. And my connection with you is exactly because of Haile Gerima. I was in grad school studying film in D.C.. I interviewed him for a class, and he said, “You need to go to two things—you need to go to FESPACO.” I think that’s where I first met you, when Sankofa was premiering at FESPACO in 1996.

I think so—because I first went to Burkina Faso in 1992, just before you started your festival. I was invited by Clement Tapsoba and Prosper Compaoré for the Theatre for Development Festival. That’s where I met Clement—he was thinking about Écrans d’Afrique and African Screen magazine, funded by FEPACI. So we all came together for the same reason—because there was nothing. I was hungry like you. I’m a polyglot too—I grew up in Russia—languages, places, diplomacy, all of it. But in the late 90s I didn’t see any reflection of who I was.

So when I came across FESPACO, I was introduced to you through Haile Gerima and Clement Tapsoba. I remember coming to your festival. Clement said, “You could write an article for this new African Diaspora Film Festival opening in New York—they’re going to Toronto. Ask them if you can go with them.” And you gave me your pass. I found my way to Toronto and met you there.

And then—I came back to New York for a couple of years and just sat and watched every single film you curated, beginning to end. Sometimes with friends, sometimes alone, because it was around my birthday. Listening to you both now, I hear these unlikely characters who understood that our Blackness and our Negritude are vast—and that we came into being at the moment the internet opened the world. But the ignorance was profound. People used to call me a liar—“Black people don’t talk like you.” Even Black people told me to go back to Africa, with no clue how old and vast the African presence is.

So it’s a miracle that after 33 years you’re still here—still filling gaps. Because there are still gaps—what’s allowed through the gate. Tell me more about fulfilling the gaps.

RBS: For example, in Harlem, there was a moment—I don’t remember the year—when a movie theatre opened. The promoter approached us; we had some productions there. For reasons explained, the theatre folded, closed its doors. That was one of the most complicated moments for the development of Black cinema in this country. No one has said that but me. The intention was to enrich the Harlem community. The first step was to find films reflective of that community.

DNS: That’s why we were so happy to be there. We played films—we remember playing a film about you, Sundoor. We had an audience. We played a film about Katrina and invited a woman involved in that situation. We were doing something there. We were not making money because the intention was not to make money. The intention was to build an enclave that would grow gradually, enrich the community, empower the community, and be a place you could recommend to people in and out of the United States: if you have a film, you can go there. We don’t have that anymore.

RBS: We don’t have that in any other place. What has remained are festivals—like our festival. Some of us are struggling, but we are still there. And the fact that we don’t have a movie theatre—I am still old school.

RBS: In a city like New York, in Washington D.C., Chicago—cities we know—if we had a theatre with the intention of bringing Black cinema… and when I say “Black,” I’m not using the narrow terminology. We are all Black with different realities. But if you had a theatre in a good urban center with that kind of programming, it would create a different landscape. We don’t have it now. What we have is virtual platforms.

DNS: And these virtual platforms are a step towards something that I cannot define. It’s harder to create community.

RBS: Exactly. It’s not the same. But we have built communities: in New York, in Chicago, in D.C. and in Paris. People buy passes and watch as many films as they can. People interact; they have a good time. It’s empowering. When you live in a multiracial society where you are not the dominant race or financial power, you are under attack all the time—but you are the dominant culture. That’s the irony.

I worked in public schools here in New York City. I could identify issues Black kids had about appreciating their beauty, appreciating possibilities. I remember a film we showed—directed by Euzhan Palcy—and it had cues about education: “education is the door that leads to a better life.” Some people say it’s cliché, but in a classroom where kids tell you, “I don’t have much at home, no one tells me to read, no one takes me to a museum,” you realize the need. I brought African diplomats to a school once—Washington Irving High School—and you see what it does. But I don’t know what the future holds. Things are going differently.

When we go back and talk about Clement, Diarah was on the jury at FESPACO in 2003. We were exposed to the wisdom of Gaston Kaboré, important in African cinema, and former president of FEPACI. These are people you cannot dismiss.

And there was the question of distribution. The festival began in 1993. Filmmakers asked about distributors. We were honest: we didn’t know distributors, besides California Newsreel, which was an educational market. They wanted something larger. So we explored distribution. A year later—in 1994—ArtMattan Films was born. Today, we have more than 100 titles from Africa, the Caribbean, and Europe—all about the global Black experience.

I remember when you first started distributing. You kept the tapes on a table—VHS, I’m sure. I got Kirikou from you—my kids played it to death. These are classics you curated. You are part of that incredible history of African cinema and distribution. Please go on.

RBS: We distribute films from newer generations too—films with powerful stories. Some deal with forgiveness in turbulent war contexts. La Pirogue—immigration, people on a boat risking their lives looking for El Dorado. These films deserve theatrical releases, but we didn’t find theatres easily. We relied on universities and festivals.

Another complicated issue is film criticism. Clement was a very good friend. We could rely on him. He was honest—he would say what worked, what didn’t, and where a film could be improved. That’s how you grow. Nowadays, it’s hard to find critics doing that work—especially for African films. There isn’t glamour, money behind distribution and rollouts. You might be the only person in a theatre if you go to critique an African film. No red carpet. So the whole thing has to be elevated.

And that’s what you’ve been doing for thirty-three years—elevating the Black presence and the Black experience on screen. I think your time has come now, because the new generation is getting little tidbits on Instagram—instabytes of history we had the privilege to encounter in full films. Your catalogue needs a push so people can get the full story.

I’m pleased to say we just launched a VOD platform—ArtMattanTV—accessible in the US and Canada. It’s brand new. We are putting films there, creating programs, enriching them with background information, capacity to learn more about the films. Hopefully, we want to create a community online, if that’s possible, so people can exchange ideas and discuss the films as they watch. We have ambitious plans.

Congratulations. That’s huge—and it’s exactly what the archive has been waiting for.