Banner photo: Meklit Hadero and Alsarah with The Nile Project (Eyre)

The acclaimed Ethiopian-American artist Meklit Hadero released her new album A Piece of Infinity on September 26 on the Smithsonian Folkways label, and recently released sessions of these new recordings, delighting her growing fanbase. She is on a mission to express the continuities of Nile music in Africa and the diaspora, sealing her commitment to drawing from the Nile songbook.

Born in Addis Ababa, Meklit’s family fled Ethiopia during the Derg committee rule, the military junta that overthrew the monarchy in Ethiopia on 12 September 1974, with violent purges towards monarchists by Mengistu´s socialist regime. Her family took refuge in the U.S., where she went on to graduate from Yale in Political Science, finally settling in the San Francisco Bay Area. Opting to follow her bliss in music with the blessing of her family, she was exposed to the soul, folk, punk and funk scenes, and was able to strategically lead and establish the Arba Minch Collective, uniting Ethiopian artists in exile, ensuring she remained connected to her homeland. This connection has ensured Meklit is in constant dialogue with her roots, firmly grounding her repertoire and musicianship. Her songs seem familiar, but listening over time, her constant engagement and study of her Nilotic roots have ensured constant transformation and have manifested in an undeniable confidence.

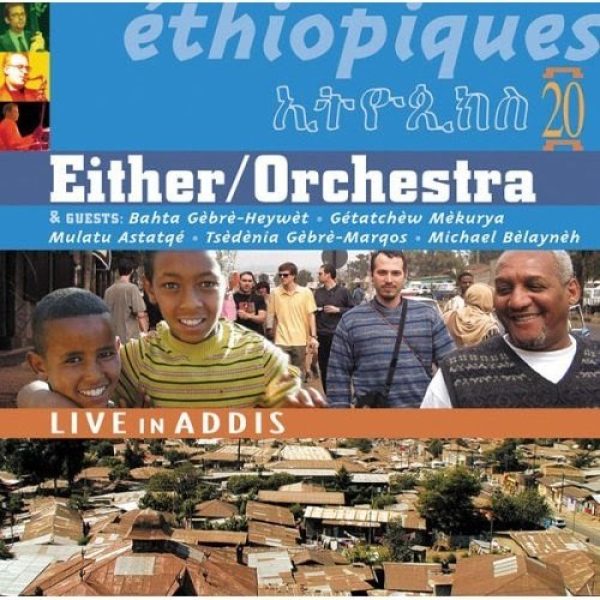

Her traditional Ethiopian jazz roots, instrumentation is an organic blend of blues, jazz, and other Afro-Latin rhythms, has given her sound a vocal texture and range that fluctuates between chromatic and pentatonic (five-tone) scales used in Ethiopian music and more familiar seven-note heptatonic scales. On A Piece of Infinity, Meklit effortlessly straddles these registers confidently; she has the best of all the musical worlds. She is comfortable singing divine praise in Ge'ez, the ancient South Semitic language from Ethiopia and Eritrea–used as a liturgical language, primarily for the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo–and also as a songstress in the Ethio-jazz mold, and everything in between. The genre traces its roots to the 1950s and 1960s, where the sound reached a "golden age.” During the era of "Swinging Addis" in the late 1960s and early 1970s, luminaries of the genre included Mulatu Astatke, known as the"father of Ethio-jazz," who studied at Trinity Music School in London and then went on to the Berkeley School of Music, combining two different musical styles of European Western and African American jazz.

Others who have contributed to Ethio-jazz include Alemayehu Eshete, Hailu Mergia, and Mahmoud Ahmed and Muluken Mèllèssè (subject of Volume 31 in the Ethiopiques compilation series, out this fall). Mulatu’s distinct smoky sound was originally forged using vibraphone, keyboards, horns and drums. Traditional Ethiopian instruments like the single-stringed masīnk’o and the lyre-like krar also found their way into the mix, along with wind instruments such as the washint (bamboo flute), and percussion instruments like the double-headed kebero drum, the begena (a large, harp-like instrument), the tsinatsil (sistrum) and more. These innovations identify this bluesy sound as Ethio-jazz, for all its borrowings, plainly indigenous to the place where it was created.

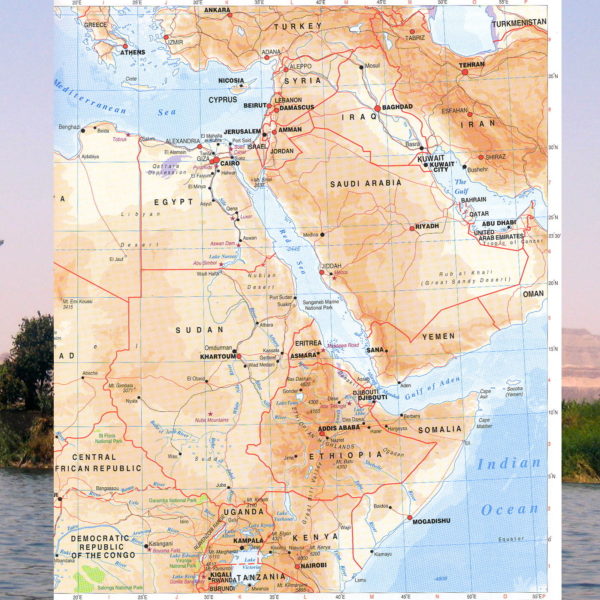

Meklit came of age anew over the past ten years as a co-founder of The Nile Project, where she embraced a new landscape of regional genres and awakened a desire to know more. Her musical journey evolved into a decolonizing methodology in a region that has seen an unfair share of ethnic violence, environmental plunder, bad governance and rationalization. Music, that evanescent commodity gifted to all peoples of the world with no beginning or end, could reconnect participants, divided over centuries of colonial expansion, conquest and slavery. Sub-Saharan Africa, as a colonial cartography, was a phrase coined in 19th-century European geography to draw a racial boundary through the continent, dividing “North Africa” (coded as Mediterranean, Semitic, ‘white’) versus “sub-Saharan Africa” (coded as Black, tropical, ‘primitive’).

The so-called division between “North” and “Sub-Saharan” Africa is a colonial fiction that disconnected the heirs of Nile Valley civilization as somehow separate. Meklit and her cohorts in The Nile Project challenged the myth of Africa as “without history.” In fact the participants' ancestors' music tells a coherent narrative because our ancestors traversed the fertile Sahara for millennia and discovered that they belong to one living cultural field. That imaginary sub-Saharan line erased the long continuity of related African civilizations — Nile Valley, Nubia, Kemet, Kush, Great Zimbabwe, Mali, Ife, Benin — and pretended that the Sahara was a civilizational wall rather than a corridor of exchange.

Meklit would discover this in her foundational years of the Nile project and imagine Africa as a single civilizational continuum on the continent and beyond in diaspora. The Sahara was never a barrier; it was the “inland sea” across which ideas, genetics, and spiritual systems moved freely. The musicians of the Nile Project focused on environmental issues, but also identified themselves as having a common mother in the Nile, formally separated from each other in the partitioning of Africa in the colonial experiment, but reunited in a powerful touring band. Reunited as a collective, they reintegrated indigenous sounds into the African music landscape, and Meklit´s own eclectic brand was born in blending her own West Coast Punk, Rock, with nuances she gleaned from Burundi, Rwanda, Egypt, Sudan, Uganda instrumentalists and vocalists she toured with.

Meklit describes her new studio album A Piece of Infinity as “an invitation to think, to love, and to groove. Celebrating the rich musical traditions of Ethiopia,” with a songbook in languages of her mother tongue, Kembaata and Amharic, as well as Oromigna and English. From songs of longing and love to children's riddles and original compositions, Meklit traverses expansive sonic ground that offers just a glimpse of the infinite complexity of Nilotic culture. Her inspiration has been the knowledge she gleaned during her experiences on The Nile Project, taking her audience deeper into her own Asmari/kambaata folk roots, but innovating along the way with the freedom that is improvisational jazz. This album showcases her clear choices of genres and diverse languages found in Ethiopia, and explores folk songs reimagined through modern arrangements, featuring collaborations with harpist Brandee Younger and flutist Camille Thurman.

After what seemed like an eternity of mixed scheduling, bad internet signals, family crisis, and a grueling time difference between San Francisco and Nkhata Bay, I was finally able to talk to Meklit, and the conversation flowed like honey.

Mukwae Wabei Siyolwe: You are amazing. I think working with so many different types of musicians from all over the world for so long, what I've seen is that there's no beginning, there's no end to Black music, in the sense that the genres are just like a flavor, you know. I'm sure it was really exciting, like you said, for your artists to sort of get into another flavor.

Meklit: I co-founded a project about the music of the Nile River. We did a ton of touring on the continent, in Europe and North America. Everywhere we were going, we were asking the question, “With whom do you share an ecology?” and “How does knowing them or not knowing those people shape the way that we share resources and information, and connect across our communities?” That project had me in a tour van with Ethiopian traditional musicians, very dear friends, Salam Nesh Zemeneh, Dawit Sioum, Andris Hassan and Jorga Masfin. It was like being in school, and it was a level of being in school that I had never had before. Because, of course, I grew up with that traditional music, but traditional musicians in Ethiopia play music from many, many different ethnic groups.

You know, that's what it is when you go to an Azmari Bet traditional gig, but you're going to hear music from twelve different tribes and ethnicities in Ethiopia. I just received it, and I began to understand that part of the reason these traditional songs hold power is that millions of people have poured their love into them. And so when you sing those songs and perform those songs, it's like you're riding on these currents of power. And so that for me was irresistible. That project made me really rethink. I grew up in the States. I was born in Ethiopia, and I came as a refugee when I was a kid. But this, mixing jazz and Ethiopian music, has been a very natural expression of who I am. But at the same time, The Nile Project really showed me what traditional music could be in a contemporary context. It was as much a definition of modernity as any mixing of jazz, traditional, and Western music.

It just completely reshaped the way I thought, because those traditional musicians were some of the most experimental artists that I had ever encountered. They were ready to collaborate, like ready to just be like, “Oh, you're a punk musician? Let's see. Like, what is that? Like, oh, you're like, okay, Congolese music? Yes, let's go.” They were just ready, and so I just saw traditional music differently after that experience. It was just something that was so living and so vibrant and so ready to meet the moment. And that's what made me want to do this record. So it's just been beautiful to see just how all of this has just sort of come together really recently, full on, like we actually know each other now.

Let the circle be unbroken, and I'm so excited to hear more about that.

I really hear you. It is all about the circle. For example, my saxophonist, whose name is Howard Wiley, and he's a genius Black American artist. He's like a channeler of Black American sound. He grew up in the Black community in Oakland, California. When we talk about why we play music with each other, we say it's because our folks are folks. It’s all about the circle, like, Ethio-jazz wouldn't exist without John Coltrane.

There's actually a story about who the godfather of Ethiopian jazz, Mulatu Astatke. When he was living in New York in the ‘60s, he was playing with a lot of Cuban musicians. And he saw how Afro-Cuban musicians were bringing their traditional music together with jazz. And then he was playing with John Coltrane. And there's this famous encounter, where John Coltrane was like, “Man, you got to bring your traditional music into this. Like, what would that be?” And they had a conversation about it that was deeply inspiring to Mulatu Astatke. There is the circle, because Mulatu Astatke's music then comes back to the U.S., and to the world, and inspires so many Black musicians. If you go to Brazil, they love Mulatu Astatke there. There are many places where Ethio-jazz becomes just another part of the circle.

And then what comes from that, you know, the circle, as you said, is endless. It continues. The ways we can see each other, know each other, and be inspired by each other are endless. It's beautiful.

It’s the call and response. I have discovered the Nile to Limpopo continuum in music, sounds, frequencies, and linguistically in namings. For example, my given royal name in Barotseland is Wabei. It's an Ethiopian name Wubbe. Yes, but it's also a Southern African name. And it means the same thing all the way from the Nile to the Limpopo: beautiful, joyous, happy in both Amharic, Zulu, Xhosa, and SiLuyana. In Amharic (አማርኛ) its roots are wäbä, wäbey, wäbi, and can mean beauty, delight, radiance, joy. In Geʽez (ግዕዝ), Ethiopia’s classical tongue, the root wab (ወብ) and in siLuyana, within our royal court speech and praise, Wabei is a name that encodes qualities of spirit and attributes of kingship.

For a princess, “beautiful/joyous/happy” is not a casual label. It is a destiny title, inscribed in song and etiquette. So in all our tongues, my name functions as an affirmation: beauty and joy as a state of being and as a responsibility. A name carries the same resonances — beautiful, joyous, happy — in both Amharic (a Semitic language of the Horn, closely tied to Geʿez, Ethiopia’s liturgical tongue) and siLuyana (the Barotse royal court register) does not just coincide randomly; it is born out of a common ethos. So I've traced it. I traced a continuity of our migration, and we are the same people. Sonwabile means we are happy. There is a huge TikTok hit by the infamous Kabza de Small & DJ Maphorisa called Ásibe Happy featuring Ami Faku in South Africa called Sonwabile, translated as “we are happy.” This song illustrates that we are really one people with just different flavors. So I'm just really excited about all the work that you're doing, in terms of that reality you discovered in The Nile Project. How did that come about?

The Nile Project came about in 2011. We started that together with Mina Gergis, who is an Egyptian ethnomusicologist. The project was active until 2018 and had a deep seven-year cycle focused on the music of the Nile River. The first time we got together, the musicians, there were 18 of us on a residency. We were in Aswan, Upper Egypt, and we were at a cultural center called Fekra, which was between the low dam and the high dam. When I say I found family, it was meeting each other, collaborating. We created dozens of songs together. We would have these sessions where people would take turns teaching about the traditional music of the place where they came from, and the next day, you would be a student. A kind of musical growth and expansion began. So we were learning about quarter tones and those Ugandans on the drumming. Whoa! The sophistication of the drumming was just mind-blowing. Of all the experiences of the Nile project, I feel like that one, that first meeting and realizing that we found family, that we were family, that we could relate to each other in this way through music. And then seeing how euphoric it was when we brought that music to people, it was really a very powerful project.

So that was the inspiration specifically for this album, A Piece of Infinity?

Yes, it started from being on tour with The Nile Project, and I started to really understand the infinity of Ethiopian music. I just felt the infinity of it, and I wanted to reflect some small part of that, and to make a record of this. And then at the same time, I had this experience where my first record in 2010 called On A Day Like This had one traditional song called “Abaimado.” And then the second record, called We Are Alive, March 2014, had a hit called “Kemekem” ( I like our afro), and they were both hits in Ethiopia, and the videos went viral there. I felt like it all opened something up in my relationship to Ethiopia in this way, that was like a million open arms.

It also inspired me at that time, like there's more to do here. There's more to explore here. There's more to know here. And then those things together, I was like, okay, I'm making a record of traditional songs. I'm going to reinterpret them. Mulatu Astatke said to me, he said, “You know, find your contribution and keep innovating.” It was all those things together that made me want to make this record. And then in 2019, I started a collaboration with a space called Women's Audio Mission in San Francisco. It's the only studio in the world entirely built and run by women, and they were like, “Come make this record here,” and they found the funding for the whole thing. And then Smithsonian Folkways came along, and they were like, we want to collaborate too. And so the whole thing just kind of grew organically from the ideas to finding the collaborators, to finding the right way to bring it out into the world.

Incredible. So what do you want to happen with this new album?

People ask me these questions, and on some fundamental level, my strategy is to be myself.

Exactly.

And to follow my inspiration, because I know that if I feel really excited about something and I have a strong inspiration about it, and it relates to the power of the community and a communal power, I know what will happen from that. It will be a good thing. So there's a part of me that's like, my strategy is to be myself. You have to plan and you have to make goals, but then at the same time, you also know, as a human, I'm humbled to life. And in the way, I also know that you make what you make inspired by your heart and your deepest soulfulness, and you can't control the outcome. What I want to happen is that I want this to be aligned with what is deepest in me, and I hope that it aligns with the depth in other people. That's what I hope.

That’s incredible. What are the songs and the themes of some of the songs on the album?

One of the themes that runs through the album is actually women's and girls' music. And there are several songs in that vein. So, for example, Abeba Yehosh.

This is an Ethiopian New Year's song, and it's traditionally sung by women, by girls. They go house to house with yellow flowers and sing “Ababa Yehosh.” And people, you know, give them tips or a little bread. And it's the way these girls welcome the new year and also sing to their community in honor of the new year, and this is a very powerful song. There's also a song on the new album called “Dale Shura,” which is Oromo. And that's a women and girls song where it's the character of a girl singing for her cows and for the land and for the rain and the blessings of the rain.

I was also able to collaborate with the legendary, iconic poet Alemtsehay Wedajo, the first woman director of the Ethiopian National Theater. She's a poet, a lyricist, a theater director. She's just coming up on a 25th anniversary of the Aitu Cultural Center, which is a center that is named after Empress Taytu, who is Menelik's wife and a very powerful warrior woman. Alemtsehay Wedajo has had the Aitu Cultural Center for 25 years, and she's written lyrics for every Ethiopian legend you can imagine. And she wrote these lyrics for me.

That's amazing.

Then there is a song called “Lefeqer Enegeza.” That song came out as a single in advance of the record. Remembering that this was all recorded at Women's Audio Mission, where every single engineer was a woman. Mary Ann Zahorsky was the recording engineer. Gloria Kaba, who is this wonderful Ghanaian-American music producer, mixed everything and Jessica Thompson, a mastering engineer who mastered everything. So this theme of the power of women and girls and our contributions is also running through this record.

I'm blown away. You are so blessed to have your own lineage behind you. Because, amazingly, you've been able to maintain that very tight contact with your homeland on a creative level, not just like on a familial level because you were born there, but you were raised in the U.S., and you've still been able to maintain that connection.

I think that there was an experience that happened in kind of 2009. I went to Ethiopia for the first time as an adult when I was in my early 20s. We left as exiles, and we couldn't go back for many years. And then when we were finally able to go back, I started to have this experience of doing music, and I founded a collective of Ethiopian diaspora artists, we were poets and photographers and filmmakers and musicians and visual artists. We went to Ethiopia together, we did several trips together, and we collaborated with traditional and contemporary artists. And this started in 2009. It was so wonderful, and together, we had this experience. We had learned our culture from our parents through their experiences and their memories, and the stories of their lives. And together through these trips, we started to understand that Ethiopian culture continued to evolve and change. And the only way to really understand it was to go and just keep going there. And so and to refresh, I started going pretty often, and that really helped me to stay connected.

I've got like a personal connection with Salem Mekuria and Haile Gerima. Were they part of that group?

Yeah, Salem and I have known each other forever. I used to stay with her when I would go to Boston. I would call her up and be like, “Can I stay with you? My darling.” She's amazing. Her daughter and I were in the same year at university. And so that's how I know her.

I know her in a different way from the Pan African Film Festival FESPACO in Ouagadougou, where we first met. These are amazing mentors that you have as well.

Yes, Selim's daughter, Samra, and I were closer because they were in Boston, and she would come visit and bring food. And then Samra would come find me and be like, “I got home cooking. Come on, let's go to the dining hall. We're going to have injera.” So we would go to the dining hall and warm it up in the microwave and just sit in silence eating because the food was so good from her Mama. Salem.

I understand. I grew up with a lot of Ethiopians in Cairo, with a lot of Ethiopian exiles who all called me Wubbe. You know, well, the Ethiopian ambassador and his wife were like my godparents in Cairo. I just had Ethiopians in my life forever, and Haile Gerima was a mentor. At Howard University, I sought him out, are there were no Black professors when I went to film school at American University in DC. I totally appreciate and understand the beautiful community that you have, and that you really support each other. I think definitely part of your success is that you do have that strong foundation.

Absolutely. I feel so grateful for the support of Ethiopian communities and Black communities and for the African communities and the ways that they all intersect. For example, I remember one time, I think in 2015, the video for the song “Kemekem,” (I Like Your Afro) came out, and it took me a long time to record that song. I learned it from a traditional musician who lived not too far away from San Francisco. And when I learned that there was a traditional song about the person with the perfect Afro, I was just like, That's for me. And so when it came out, I knew that that song was going to be a pan-African love song also. I knew that it was going to touch something, and it was like rocking in Brazil for the Black communities there. And then there was a Black Lives Matter organizer who was working out of their Oakland office. And they came up to me, and they were like, you know, that song was always rocking with us. There was power in that song, like what you were saying about how the connection is endless and the circle keeps circling. Right?

Absolutely. How does your family respond to your success? Are they supportive?

Oh, they’re so supportive, but it took awhile. At first; they were like, “What are you doing?” But then they saw that it was working. And when they saw that it was working, they were like, “You know what? We're willing to be surprised by you.” As they got older, they said, “It’s your life, you live your life.” My father, for example, still comes to my shows and gets up on stage. There's a song on the new record called “Gifata.” It is a traditional song from the place he comes from in Ethiopia called Kambaata.

It’s a communal celebration song. We actually played it live at a show that he was at. I said, “You're going to come up and sing it with me?” and he was like, “Honey, I need a staff. I can't come on stage if I don't have a staff.” And I was like, “Well, what about this?" and behind him, completely unbeknownst to both of us, was this giant curtain rod that was actually very light. And it had this tape twisted on it, in this spiral pattern that was beautiful. And it was tall, it was maybe like nine feet tall. And I said, “Well, what about this?” He said, “That's perfect.

So we got him a staff and he did all of that beautiful movement with the traditional songs and everything. He did the traditional dance. It's not an Eskista (Amharic: እስክስታ), which translates to "dancing shoulders.” They don't do Eskista in Kambata. It's a different way of dancing, but he did the Cushite Kambaata traditional dance with the staff on stage. And so, how can you beat that? You can't beat that. That's just the best.

Wow. Well, is there another song? Can you tell me about any other song on the album we should feature?

I always go back to “Tizita,” because “Tizita” is one of the most classic songs from the Ethiopian repertoire in Amharic. It’s the style of a song of longing and nostalgia. And it was really interesting because that's the song that had me asking, “What is a song?” Is it a melody? Is it the story? And what I felt about “Tizita” is that it is a feeling and a story. And if the feeling and the story were there, that “Tizita” could carry. And so we really took a wide berth with the music of “Tizita.”

I'm so blessed to be able to collaborate with Kibrom Birhane (sometimes spelled Kibrom Berhane), who's this incredible Ethiopian and Tigrigna multi-instrumentalist. He’s like my brother. He's in the band, he plays piano, masenko, and krar. And for example, he's playing krar on “Lefeqer Enegeza” and piano on “Tizita.” And we totally reinterpreted that song, and Brandi Younger is featured on it as well. He’s just a genius of jazz harp.

I've got so many more questions, but we did it. Thank you so much, we will go on and on…

We will. Thank you, Mukwae.

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles